Dismantling Icons

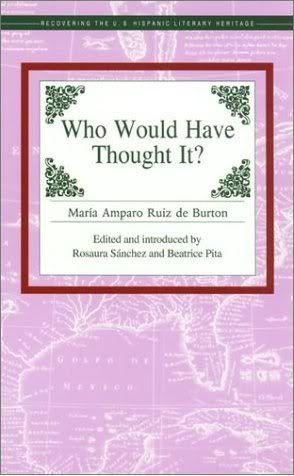

Toward the end of the introduction to Who Would Have Thought It?, editors Rosaura Sanchez and Beatrice Pita write that Ruiz de Burton’s work, in their estimation: “carries out an incisive demystification of an entire set of dominant national myths, many of which are unfortunately, still very much with us today” (lvii). While critical perspectives of the United States and its “glorious government” (Ruiz de Burton 271) have proliferated throughout the years, Ruiz de Burton’s novel does more than simply “satirize American politics…through mocking of divisive political discourses and practices of the period” (Sanchez and Pita xv-i); the recovery of her text serves as an agent of “demystification” for one of America’s long-revered icons: President Abraham Lincoln.

Toward the end of the introduction to Who Would Have Thought It?, editors Rosaura Sanchez and Beatrice Pita write that Ruiz de Burton’s work, in their estimation: “carries out an incisive demystification of an entire set of dominant national myths, many of which are unfortunately, still very much with us today” (lvii). While critical perspectives of the United States and its “glorious government” (Ruiz de Burton 271) have proliferated throughout the years, Ruiz de Burton’s novel does more than simply “satirize American politics…through mocking of divisive political discourses and practices of the period” (Sanchez and Pita xv-i); the recovery of her text serves as an agent of “demystification” for one of America’s long-revered icons: President Abraham Lincoln.Who Would Have Thought It? contests the commonly held idealization of Lincoln as a leader who “built the Republican Party into a strong national organization” (whitehouse.gov par 7), as a kind-hearted man who was “flexible and generous” (par 9), and living by his self-fashioned credo: "With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in” (qtd in whitehouse.gov par 10).

When Julian, the story’s protagonist, first confronts the President over his dismal from the military, Lincoln appears to be oblivious of the order he himself signed: “I haven’t dismissed you. Or, at least, I don’t remember. What is your name?” (Ruiz de Burton 215). After Julian convinces him that the charges are baseless, Lincoln demonstrates little, if any, urgency to rescind the order. As days pass, the matter remains unresolved and Julian heads back to the White House. During their second meeting, Ruiz de Burton portrays Lincoln in an all together different manner. No longer exhibiting a lackadaisical and nonchalant personality, the President demonstrates indecision and “look[s] towards the high officials, as if anxious to ascertain their opinion” (Ruiz de Burton 240). Ineffectual and unaware, Ruiz de Burton depicts Lincoln as someone much less than the monuments and history books would lead us to believe.

Who Would Have Thought It?, then, works in contradistinction to our mythologized version of Abraham Lincoln; and the importance of a characterization that is antithetical to our traditional understanding of the past cannot be understated. As Barthes once wrote: “Myth deprives the object of which it speaks of all History. In it, history evaporates” (151). To re-inscribe a more proper history, the icons that myth erects must be dismantled; and certainly, with his face stamped upon pennies and printed upon bills, Lincoln has become a mythic figure devoid of historical accountability.

While Ruiz de Burton’s novel demystifies aspects of Lincoln’s character, there is one glaring omission regarding of the former President that she glosses over: he was a racist who cared little about the well-being of African-Americans. In fact, Lincoln made law the Emancipation Proclamation for political ends, not humanitarian ones. Writing to a friend, he referred to slaves as “creatures” (qtd in Zinn 188) and in a response to a 1862 article in the New York Tribune wrote: “If I could save the Union without freeing any slave, I would do it...What I do about Slavery and the colored race, I do because it helps to save this Union” (qtd in Zinn 191). The law decreed slaves in the Confederacy free; if rebel states rejoined the Union, the same law would allow them to continue their practice of slavery.

Ultimately, it is the novel’s scoundrel, John Hackwell, who provides the most precise estimation of Lincoln’s leadership:

And with perfect sang-froid we can see a cabinet officer make a cat’s paw of a President! And we say we are the ‘model government,’ because, as long as the mob is cajoled, no matter how much individuals are tyrannized over, a cabinet officer can crush anyone opposing him and make it all right with the President by telling him and the mob that it is done for the glory and interest of the people. (Ruiz de Burton 271-2)

It would appear that even our most celebrated leaders, regardless of how rosy the lens with which we view them, fail to meet the mythic standards and noble expectations we hold them up to.

Works Cited

Barthes, Roland. Mythologies. Trans. Annette Lavers. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus, &

Giroux, 1972.

Ruiz de Burton, Maria Amparo. Who Would Have Thought It? Houston, TX: Arte Publico Press, 1995.

Sanchez, Rosaura and Beatrice Pita. Introduction. Who Would Have Thought It? By Maria

United States. The White House. Abraham Lincoln. 12 Mar 2007. 17 Jan 2008

< http://www.whitehouse.gov/history/presidents/al16.html>.

Zinn, Howard. A People’s History of the United States: 1492-Present. New York, NY: Harper-

Giroux, 1972.

Ruiz de Burton, Maria Amparo. Who Would Have Thought It? Houston, TX: Arte Publico Press, 1995.

Sanchez, Rosaura and Beatrice Pita. Introduction. Who Would Have Thought It? By Maria

United States. The White House. Abraham Lincoln. 12 Mar 2007. 17 Jan 2008

< http://www.whitehouse.gov/history/presidents/al16.html>.

Zinn, Howard. A People’s History of the United States: 1492-Present. New York, NY: Harper-

4 comments:

Every moment of action with reference to History reorganizes, re-members History into a history that is dressed up as History and will affirm the action in principle before-the-fact with a principle created after-the-fact.

Editorial note: para. 3, [sic] dismissal vice dismal.

I am highly interested in to read further of this book. While it is somewhat hard to believe that a low-level military would have executive accessibility (even in 1860), de Burton's characterization of Lincoln as "[i]neffectual and unaware is all-to-telling of bureaucrats; both past and present. I suspect de Burton must have done some critical research, beyond mere speculation, to surmise such a damning, dare say: embarrasing, label. Whichever way the author contrived such a conclusion, either through speculation or educated guess, it is spot-on. Most civil servants would concur that shit rises to the top. Essentially, the more of an impotent 'yes'-man one becomes the higher they rise in the political food-chain. Thus, beoming "someone much less than the monuments and history books would lead us to believe".

Ruiz de Burton was a contemporary of Lincoln. Her husband was an American military-type & she met Abe on several occasions. PS: Access to executives was that open...hence the eventual cap in Lincoln's cerebellum.

touche, douche!

Post a Comment