Notes & Half-Thoughts on the Rhetoric of Love

Rudimentary observations.

From Chela Sandoval’s Methodology of the Oppressed: “Writers who theorize social change understand 'love' as a hermeneutic, as a set of practices and procedures that can transit all citizen-subjects, regardless of social class, toward a differential mode of consciousness and its accompanying technologies of method and social movement.” (140)

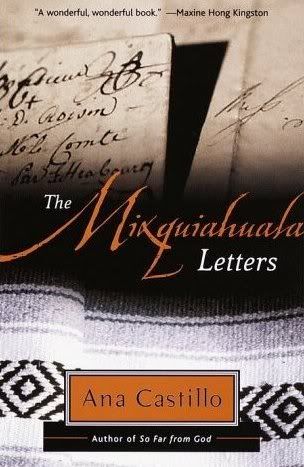

From Chela Sandoval’s Methodology of the Oppressed: “Writers who theorize social change understand 'love' as a hermeneutic, as a set of practices and procedures that can transit all citizen-subjects, regardless of social class, toward a differential mode of consciousness and its accompanying technologies of method and social movement.” (140)From Ana Castillo’s The Mixquiahuala Letters: “Love? In the classic sense, it describes in one syllable all the humiliation that is born to and pressed upon to surrender to a man.” (117)

From Ana Castillo’s The Mixquiahuala Letters: “When I say ours was a love affair, it is an expression of nostalgia and melancholy for the depth of our empathy. We weren’t free of society’s tenets to be convinced we could exist indefinitely without the demands and complications on aggregated with the supreme commitment to a man. Even greater than these factors was that of an ever present need, emotional, psychological, physical…it provoked us nonetheless to seek approval from man through sexual meetings.” (45)

From Ana Castillo’s The Mixquiahuala Letters: “When I say ours was a love affair, it is an expression of nostalgia and melancholy for the depth of our empathy. We weren’t free of society’s tenets to be convinced we could exist indefinitely without the demands and complications on aggregated with the supreme commitment to a man. Even greater than these factors was that of an ever present need, emotional, psychological, physical…it provoked us nonetheless to seek approval from man through sexual meetings.” (45)From Chela Sandoval’s Methodology of the Oppressed: “My commitment to the development of a neologism such as that represented in this nexus of terms reflects my belief that we need a new, revitalized vocabulary for intervening in postmodern globalization and for building effective forms of understanding and resistance.” (6)

Sandoval’s implementation of the term “love” as a “set of practices and procedures” that will initiate or sustain a “differential mode of consciousness” with the ultimate goal of creating a “social movement” is problematic in that the rhetoric of love obfuscates her (as well as Barthes) intended message. True, the use of the term “love,” within the context of her text, refers to “the unlimited space” in which “ties to any responsibility are broken,” and thus produces “a utopian nonsite, a no-place where everything is possible” (Sandoval 140), but as one can gather from the speaker of Castillo’s text, understanding of love “in the classic sense,” carries with it much in the way of negative connotations (i.e. “all the humiliation that is born to an pressed upon to surrender to a man”). Even when Castillo’s narrator refers to the love between Teresa and Alicia, it merely signifies “nostalgia and melancholy”; worse yet, the speaker nonetheless reverts to her “classic” understanding of love because of “an ever present need” to do so.

The question then becomes, why would Sandoval and Barthes remain committed to the term “love,” when Sandoval herself informs her readers that her writing maintains a “commitment to the development of a neologism”? Wouldn’t, instead of “love,” another self-created term serve her purpose more thoroughly and with less confusion? Through the creation and development of a new word, Sandoval would enable herself to fill an empty concept with meaning, thus constructing an entirely unique mythology that is not hampered the burdens of previous semiotic connections.

This, of course, is not to say that Sandoval’s and Barthes co-opting of “love” for their respective theoretical frameworks is devoid of utility. For example, even though Castillo’s text demonstrates features of “love” that are problematic, it also incorporates aspects of Sandoval’s use of the word as well. As Sandoval writes: “another approach to loving” occurs when the subject of love chooses to drift “through, in, and outside of power” (143). Such a drifting finds a practical application in the destruction of traditional Western narratives, which, as Barthes claims, transforms “life into destiny, a memory into a useful act, a duration into oriented and meaningful time” (qtd in Sandoval 143). At the outset of The Mixquiahuala Letters, Castillo provides four ways in which to read her novel: for the conformist, the cynic, the quixotic, and the lover of short stories. In such a manner, she ruptures the linear and teleological trajectory of narrative (and books as physical artifacts). In this sense, Castillo’s “love” story develops a space where “between narrative forms…meanings live in some free, yet unmarked and wounded space, a site of shifting, morphing meanings that transform to let [someone] in” (Sandoval 142).

No comments:

Post a Comment